A Nameless EVIL

May 13, 2010

The introduction of Sony’s NEX-3 and NEX-5 has once again thrown a weird anomaly into sharp relief.

Even 20 Months after the introduction of the Panasonic G1, there is still no universally-agreed-upon term for this new class of cameras.

The defining aspects of the genre are a largish sensor size (as compared to typical compacts) plus interchangeable lenses. Yet by omitting any reflex viewfinder, and instead streaming a live digital image from the sensor, the body size can be reduced from the bulk of conventional DSLRs.

Name that Evil

Now, the most widely-known term (and the one I use) is “EVIL,” meaning “electronic viewfinder, interchangeable lens.”

A few pedants object that the Olympus E-P1 does not have a “viewfinder” in the sense of something you hold up to your eyeball (nor do the Sony NEX models, so far). But you can slightly revise the phrase to be “electronic viewing” instead, if this bothers you.

Sony: Less EVIL Than Feared

May 11, 2010

Well, the much-anticipated “EVIL” cameras from Sony have finally arrived, the NEX-3 and NEX-5.

Big Sensor, Small Camera

The fullest NEX-5 review available so far is at Imaging Resource (while DP Review has vented annoyance that they were given pre-production cameras, and so were forbidden to publish test images).

The clearest win for the NEX system is in body size—which (for an interchangeable-lens, APS-C camera) is quite impressive. I hope all the other EVIL brands are paying very close attention.

The tiny NEXes also make it apparent that zoom lenses become even more ridiculous in the EVIL segment: Compact primes are the obvious way to capitalize on the mirrorless size advantage.

So it’s a mystery that the sole pancake prime offered at launch is a very wide 16mm f/2.8 (24e). Sony clearly needs to fill out its lens lineup still—at least adding a fast “normal” lens (approximately 30mm for the APS-C sensor format).

But perhaps they needed more time to complete something competitive with Panasonic and Samsung’s well-regarded pancakes. Sony’s tiny ultrawide stands alone here, and will admittedly be intriguing for many shooters.

Sony could not resist stuffing in a few more superfluous megapixels: These models use a 14 Mp sensor. But the high-ISO results seem very decent. Not quite class-leading (even compared to Sony’s own 12 Mp sensors used in the Nikon D5000 or the Pentax K-x); but it’s clear that Samsung’s 14 Mp sensor from the NX10 is being left in the dust.

I can tell from Petavoxel’s site traffic that the Samsung NX-10 generated much curiosity wondering if it could accept an adapter for Leica-mount lenses, in M bayonet or 39mm thread. (The answer seems to be no, unless someone can show me otherwise.) But the story for Sony’s new “E” lens mount is much more interesting:

Shallowest Lens Mount EVAR?

Thanks to Sony for providing that handy sensor-plane mark on the NEX-3. Scaling from the published body dimensions, this is one incredibly shallow lens mount. (The throat diameter is pretty generous too, from what I can estimate). Even for the shallow lens register of Leica lenses, there’s about a centimeter of extra depth to allow a lens adapter.

So the good news is that mechanically, it would be possible to adapt just about any other lens to the E mount. What we don’t know yet is whether Sony will intentionally cripple this function, either by requiring a Sony-chipped lens to be attached or by having poor support for manual focusing.

The user interface of these new NEX cameras follows in the footsteps of the Olympus E-PL1, in being very “point & shoot” oriented. There is no tactile function wheel for manual control, a major downer for any serious user. It remains to be seen whether Sony expands the NEX lineup into “enthusiast” models with better manual controls.

Also mystifying is the lack of an optional eye-level electronic viewfinder. Sony has created a new proprietary accessory port, but currently it is only used for the (included) companion flash, an optical viewfinder for the superwide lens, and a video microphone. It seems impossible that Sony would deliberately handicap themselves by not including connectors for an EVF as well; so I guess we should assume that will come later.

I do respect Sony’s decision to keep the flash separate, given that ISO 1600 shooting seems quite acceptable with this NEX sensor. But again, it does make one wonder whether Sony has a brighter-than-f/2.0 lens option waiting in the wings somewhere.

Whither Pentax?

May 7, 2010

I guess this was the week for Pentax’s European executives to go rogue.

Hiroshi Onoda made some comments to the Spanish Pentaxeros website, hinting at future “more professional” DSLRs (google translation). Then, Stephen Sanderson told the UK’s Amateur Photographer that Pentax “hadn’t ruled out” a mirrorless, EVIL model.

Both statements were vague and ambiguous enough to set off a storm of speculation on Pentaxian discussion boards. Many hearts fluttered, imagining Pentax might introduce a DSLR based on a 24 x 36mm “full frame” sensor; others wondered whether they might join Olympus and Panasonic in the Micro Four Thirds camp.

Pentax Surprises Ahead?

But there’s two key facts that must always be remembered about Pentax:

- They do not make their own sensor chips

- Last year, the company almost went under

At PMA 2010, Pentax USA president Ned Bunnell gave an interview with Imaging Resource. He said plainly that Hoya, Pentax’s new corporate owners, were demanding more focus on the bottom line, and a clearer marketing strategy.

So, Pentax simply cannot build every camera its fanbase thinks might be cool.

EVIL Cameras: It’s Still 1958

April 29, 2010

The essential principle of the single-lens-reflex camera is actually quite old. Most of the SLR’s earliest incarnations are long forgotten today; but it’s interesting that the name “Graflex” derives from that brand’s early, jumbo sheet-film reflexes—dating all the way back to the 1890s.

In the middle of the 20th century, 35mm cameras rapidly gained respect and market share. But if you could time-travel back to 1958 and ask photographers how they felt about 35mm SLRs, you might be surprised at how divided and contentious the answers were.

Most would probably admit to the SLR’s advantages—in principle—over the other viewfinder styles common at the time.

There is no offset between the taking lens and some separate viewing lens. The framing of a shot is previewed exactly—which is particularly useful in macro and telephoto work. And the lens’s depth of field can be seen directly on the groundglass (albeit dimly, when apertures are small).

All these advantages might even cause our 1958 friends to proclaim SLRs as the wave of the future.

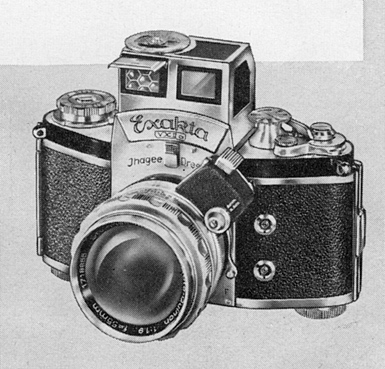

But keep in mind: At that time, the leading 35mm SLR brand was the Exakta, from Dresden, East Germany.

Exakta SLR, 1959

This was a nicely-finished camera, capable of taking fine photos. But its operation was rather clunky. For those who wanted to shoot quickly and spontaneously (which after all, was the forte of 35mm compared to larger formats), SLRs could not compete with rangefinder cameras. Decades of improvements had brought rangefinders to quite a high level of refinement, and they fully dominated the era’s 35mm marketplace.

Before the shutter opens, an SLR’s mirror must flip up out of the way. But in these early models, it did not drop down again afterward—not until the film was advanced. The resulting viewfinder blackout was disorienting, and made it quite hard to follow action.

Also, for a clear, bright groundglass image, an SLR’s lens ought to be at its widest aperture. But ordinarily, it must then be stopped down to a smaller working aperture before making the exposure. Doing that manually for every single shot becomes kind of a pain. Early SLRs struggled with this problem, and manufacturers created numerous rather half-baked solutions to it.

In retrospect the answer was obvious: just design an instant-return mirror and an instant-reopen lens diaphragm. Yet throughout the 1950s, a puzzling thing happened: All the elements of the solution existed somewhere; yet no camera maker ever put all the pieces together.

Many Exakta lenses used an external, spring-loaded plunger aligned in front of the shutter release; the photographer’s finger pressure on this closed the diaphragm. The Praktina of 1954 (another East German brand) pioneered the first instant-stopdown linkage built inside a lensmount—though needing a separate, manual lever to reset it.

But when it came to instant-return mirrors, German camera-makers had a strange resistance to them. Exakta would not redesign their SLRs to include one until 1966.

An instant-return mirror appeared in the 1954 Asahiflex, predecessor to the Pentax. Several other Japanese brands quickly adopted the innovation. But they still wrestled with the diaphragm problem. Many brands used a mechanism that stayed closed down after the shot, dimming the viewfinder until it was reset.

So, it’s rather understandible that many 1950s photographers found SLRs exasperating—and assumed they would always stay that way.

Finally in the spring of 1959, three new Japanese SLRs were introduced: the 120-film Zenza Bronica, the Canonflex, and the Nikon F. All made the breakthrough of combining the two essential features—the instant-return mirror and the instant-reopen diaphragm.

The Dawn of Usable SLRs

Although Canon’s first SLR proved an evolutionary dead end, the Nikon F was an instant classic (and its lens mount lives on, in Nikon’s DSLRs today). It cemented Nikon’s reputation as a top-tier camera maker; and it announced the arrival of the Japanese as the world’s new camera-design leaders. And within a few years, the two SLR innovations were practically universal among Japanese brands.

So—how does all this ancient history relate to the current wave of EVIL cameras? (“Electronic Viewing, Interchangeable Lens.”) Well, I believe EVIL stands at a similar crossroads today.*

In principle, we know electronic viewfinders offer certain advantages:

Potentially, they can give a much larger and brighter image than the cut-down reflex viewfinder in an APS-C camera. Histograms or any other information can be overlaid on the live image (and be easily reconfigured, via menu or firmware updates). Depth-of-field preview can be brightened electronically, for easier viewing. And instantly magnifying a portion of the frame eases focusing manually when desired.

Electronic viewing opens up possibilities for unconventional new body designs—ones that might be innovative, less obtrusive, and more easily pocketable.

And in principle, (relatively) larger sensors ought to offer no-compromise shooting at higher sensitivities—say, ISO 800, at least.

A midsized image format, with no reflex mirror getting in the way, should stimulate nifty lens innovations, too—imagine shrunken-down rangefinder-type designs. An f/1.4 normal lens could be half the size of its 35mm equivalent! (If the purpose of larger sensors is enhanced low-light shooting, why not fully capitalize on this?)

But the EVIL cameras of today are, in their own way, 1958 Exaktas.

We are beginning to glimpse the great potential they offer. But all the current implementations are crippled by maddening omissions and flaws.

The Olympus VF-2 is the nicest electronic viewfinder currently available. But EVFs must continue to improve in speed, clarity, and low-light usability before they can replace optical viewfinders entirely. And ready access to magnified focusing is essential—something the Samsung NX10 seems to have bungled badly.

“Faux-SLR” body shapes are boringly unimaginative, and needlessly large.

To date, Micro Four Thirds has only delivered a single camera with adequate high-ISO performance (the Panasonic GH1)—despite trumpeting this as the key performance advantage of larger sensors. (The GH1 also uses the only µ4/3 sensor to allow 3:2 framing without penalty.)

Likwise, the Samsung NX10 gives sub-par high-ISO performance compared to other APS-C cameras, such as those using 12 Mp Sony sensors. Pixel counts higher than this simply become counterproductive.

Only Panasonic has delivered any native EVIL lens brighter than f/2.0—which is inexcusable, considering the wide apertures of cine and TV lenses covering similar image circles. Adapting legacy lenses to EVIL bodies remains problematic, due to µ4/3’s crop factor and Samsung’s NX design choices.

Shooting quickly and spontaneously requires an eye-level viewfinder—the history of cameras has repeatedly shown it. A touch-screen interface may look whizzy, but it splits attention between the camera and subject. Controls need to be graspable and usable by feel, while looking through the camera. We’ll have to see if Sony’s upcoming EVIL system (rumored to be called “NEX”) makes any concessions on this point.

In short, it may be quite reasonable to claim “EVIL is the future.”

But I say, “the future isn’t here yet.”

I am still waiting for 1959.

*(Some prefer “MILC”—Mirrorless Interchangeable Lens Cameras—or even “SLEV”—Single Lens Electronic Viewfinder. But why name a camera after what it lacks?)

Olympus E-PL1 at DxO Mark

April 1, 2010

DxO Labs have released their sensor test results for Olympus’s “econo” Pen model, the E-PL1.

Their tests show it having slightly worse high-ISO performance than its competitors in the “compact EVIL” segment.

The entire selling point of Micro Four Thirds is that the larger sensor offers improved picture quality, relative to typical compact cameras. DxO Mark’s “Low-Light ISO” score is expressed in ISO sensitivity numbers; and here they report that noise becomes objectionable at around ISO 500.

But the overall “DxO Mark Sensor” score falls much closer to that of a modern compact camera than to that of a good recent DSLR.

This is a disappointment, given the extra time Olympus had for developing the E-PL1; and also compared to the dramatically-better performance of its Micro Four Thirds cousin, the Panasonic GH1.

As always, note that DxO Labs tests are entirely “numbers oriented” and only analyze the raw sensor data. Handling, price, the quality of in-camera JPEG processing, etc. are not considered.

Wanting an EVIL Mongrel

March 9, 2010

As recently as 2008, the digital-camera market had essentially split into two parts.

On the one side, there were full-featured (but bulky) DSLRs. On the other, there were small (but inadequate) point and shoots.

Today, there is great excitement as camera-makers grope to find some middle ground between those two extremes. The dream is to cram better image quality and more photographic control into a sub-DSLR package.

Counting Micro Four Thirds cameras and “serious compacts,” I can think of a good dozen such models on the market now.

But for a prospective camera shopper, it’s immensely frustrating that despite all the exciting new ideas floating around, none of the current models have “put it all together.” Each seems to combine some worthwhile virtue with some head-slapping flaw.

So let’s fantasize for a moment. What if we could choose all the strong points of many different cameras, and glom them all together into a single one?

We start with the sensor, of course.

There’s a recent crop of cameras praised for a 12 megapixel, APS-C sensor of good quality—particularly at higher ISOs. You can see this in reviews of the Nikon D5000, the Pentax K-x, and the A12 module used in Ricoh’s GXR.

Interestingly, every one of these shares the same 4288 x 2848 resolution—down to the exact pixel. It’s public knowledge that Sony supplies the sensor used in the Nikon; so it’s suggestive that these are all close cousins of a particular Sony chip design.

I’d also be perfectly happy with the Four Thirds sensor used in the Panasonic GH1. It tops all other 4/3 chips in performance; it also permits native 3:2 aspect ratio shooting. But Panasonic seems to have decreed that it will only be used in their premium-priced 1080p video models. That’s okay: the Sony chip is apparently cheap enough to stick into $500 cameras.

Leica’s X1 shows that it’s physically possible to fit a great APS-C sensor into a very svelte, handsome body. (Just ignore its staggering price.) Some are sure its chip is also a Sony; although the 4272 x 2856 pixel specs don’t quite match.

I am personally a fan of the X1’s uncompromisingly retro top controls. But if you prefer a slightly more modern control layout, we might also look to the nicely-built Ricoh GRD III for inspiration.

But the weakness of the X1 is that you’re stuck with a non-interchangeable, f/2.8 lens. Obviously that won’t do.

Eventually, Sony intends to join the mirrorless APS-C party; but until then, Samsung’s NX lensmount is the only one available for a mirrorless APS-C body. Happily, there’s already a very decent “wide normal” f/2.0 pancake available, as well as adapters for other mounts.

Naturally it would be preferable to get even brighter lenses: e.g., Panasonic’s excellent 20mm f/1.7 (for µ4/3) is another half-stop brighter. And while we’re mentioning Panasonic: We would definitely want to use their speedy contrast-detect autofocus system, taken from the G-series cameras. It’s clearly superior to Olympus, Leica and Ricoh’s versions.

So, we’ve covered the “IL,” what about the “EV”?

Some prefer an electronic viewfinder to be integral with the body; but I think it’s more flexible to make it removable. When you want maximum compactness, you can leave it at home in a drawer. Or when using prime lenses, some may prefer a dedicated optical viewfinder:

Leica helpfully adds a green focus-confirmation LED to the back of the X1 camera body, which you can see in your peripheral vision when using this accessory viewfinder. But since we’re going to have a socket for an electronic viewfinder anyway… Why not have connector on the OVFs too, to light them up with a few essential display items?

While many are still wary of electronic viewfinders, there are currently several very decent EVF implementations. But, we have to give the nod to the Olympus VF-2 as the one receiving the most favorable press. It’s a 1.4 million dot display, and is nicely adjustable to different angles. So let’s include that in our EVIL mongrel:

More Dubious Fantasy Photoshoppage

Oh, and the Olympus E-Pens prove that you can have in-body image stabilization without having the camera become a chubster—so let’s add that too.

Any takers?

New Lumix G’s: Disappointing

March 7, 2010

Panasonic owes my cat Madeleine an apology.

A few days ago, when specs and images of the new Lumix G models first leaked, I made such aggravated gargling and sputtering noises that she bolted out of the room in fright.

Now Panasonic has made the introductions official; and DP Review has posted the details of the new G2 and G10, as well as a G2 preview.

Essentially, Panasonic’s old model G1 (the very first Micro Four Thirds introduction) has now been split into two new models instead.

The G10 is the lighter, de-contented version. It offers a cheapened electronic viewfinder (only 202,000 dots) and no articulating screen. It does add 720p video (which is practically mandatory in today’s market)—but only using the Motion JPEG codec.

The G2 is basically the G1 with the addition of 720p AVCHD Lite video, and a touch-screen interface. It appears to keep the same 1.4 million dot electronic viewfinder as the G1. DP Review found the G1’s EVF large and bright—but jerky and grainy in low light.

The touchscreen can select AF points, or flick through recorded photos (for reference, it has a smaller screen diagonal, but the same resolution as an iPhone or iPod Touch).

The distinction between the two video codecs is this: Motion JPEG compresses each frame individually. This gives good quality, but fills memory cards quickly. AVCHD uses more sophisticated motion-estimation between frames, and so it can achieve much higher file compression. Not all video software can handle AVCHD yet.

Anyway, let’s pause for a moment and run down all the things these two models are not:

They do not introduce any new sensor; nor do they use the proven-superior chip from the GH1.

(Imaging Resource notes that the new models have an improved processor. The new ISO 6400 setting is probably a result of this greater noise-suppressing capability. But I remain skeptical.)

There’s no native multi-aspect-ratio option; only reduced-size crops of the 4:3 area.

They are not new “coat-pocketable” compact models, as was briefly hinted. The G2 and G10 are essentially the same size as the G1.

This is quite strange, as the faux-DSLR styling of the G1 was widely criticized as too conservative and boring. If the goal is to lure over point & shooters who are put off by the bulk of a DSLR, it’s hard to see the point:

There is a new, seemingly less-expensive kit zoom. There was not any announcement of more compact, bright primes like Panasonic’s nice 20mm f/1.7 pancake.

What remains to be learned is where the pricing of the G10 and G2 winds up, compared to the recent cut-price Olympus E-PL1, or old stocks of the E-P1.

Eventually my cat did forgive me. But I’m still pretty disappointed in Panasonic.

Ricoh GXR: Huh?

March 2, 2010

DP Review’s first test of a Ricoh GXR module has alerted me that I’d misunderstood Ricoh’s naming scheme for their weird, unique lens/sensor units.

In the GXR system nomenclature, “A12” refers just to the sensor’s size (APS-C), and 12-megapixel resolution. But in giving the name of the module, you also must include the lens focal length and f/ratio. (Well. That ought to roll off the tongue effortlessly.)

So the new Ricoh module announced during PMA is also called “A12.” It’s just a different one, with a wider lens. Got that?

What I did not understand is that Ricoh is expressing all these focal lengths in “35mm equivalents.” As I’ve ranted about before, this is a needlessly-confusing convention which perverts the actual meaning of the word “millimeters.”

Anyway. Ricoh’s currently available A12 module is the 50e, f/2.5 one. That is to say, it is an inexplicably-dim “normal” lens, although one with macro focusing capability. DP Review liked the image quality of the 50e/2.5 module; but they found its autofocus speed rather poor.

The GXR module coming up later this year will be a wide-angle 28e version, also f/2.5.

It’s the pricing of the GXR body+module system which makes no sense. You could pick up a Canon S90 and a Panasonic GF1 together for nearly the same money. The only possible justification would be if you were wildly in love with the GXR’s menu system, or its $250 auxiliary electronic viewfinder. The latter scenario is questionable, since Olympus’s VF-2 is generally rated the nicest one currently available.

Also, lens speeds of f/2.8 and f/2.5 are simply unacceptable in this price bracket (are you listening, Leica X1?) Panasonic’s pancake 20/1.7 lens proves that even a bright lens (where the moving glass elements must be heavier) can have fine autofocus performance.

Count me among the many who have said, “Ricoh, I just don’t get it.”

The Road to Anaheim: Paved with Good Intentions

February 24, 2010

This year’s PMA trade show in Anaheim is over now, without much to show for itself.

To keep my life simple and my blood pressure under control, I intend to ignore all new cameras with 1/2.3″ sensors.

It’s only ones with larger, high-ISO-friendly chips that interest me.

However in that category, few actual, working products got unwrapped. I did mention the Samsung TL500 already. But otherwise, there were vague statements about future possibilities and “intentions.”

Okay, Sigma announced the DP2s and its wide-angle sister the DP1x—modest evolutions of their earlier versions. The Foveon sensors remain (larger than Four Thirds), as do their superior non-zooming lenses. But we need to wait for reviews of these models’ handling and high-ISO performance.

Samsung confirmed its lens roadmap for the NX mount. But it will be months before we see their “wide pancake” 20mm f/2.8, which is a shame. Samsung promises lenses that are “stylish and iconic,” and I’ve always wanted to be iconic. Oh wait, that was “ironic.”

Ricoh announced that soon we’ll see two more “units” for its oddball GXR system. Again, the interesting one is the non-zoomer, with an APS-C sensor, coming later this year. But its 42e normal lens is an underwhelming f/2.5. How is this supposed to sell me on the GXR system?

Hopes for any new Panasonic G-series µ4/3 bodies also failed to materialize (despite persistent rumors that something new is on the way).

An Olympus rep was bold enough to suggest that DSLR mirrors may die soon. Reflex optical viewfinders have always been a challenge for Four Thirds cameras, since the smaller image makes the groundglass so tiny. The Olympus VF-2, with 1.4 million dots of resolution, has won over some doubters to electronic viewfinders.

As for other brands joining the EVIL bandwagon, a Nikon exec coyly said that mirrorless cameras were “one solution.” Sigma dropped a mention of its “plans” to build a mirrorless system around the Foveon sensor. But the biggest buzz came from Sony’s non-functioning model of a mirrorless APS-C-sensor compact:

First, let’s be clear none of these would be compatible with Micro Four Thirds. Lenses for µ4/3 only cover an image circle of 21.65 mm. For Foveon you need 24.9mm; and for APS-C it’s 28.4mm.

So, if these other mirrorless models come to market, their options for lenses could be fragmented, with only a few manufacturer-specific choices.

The Sony lens mount shown above is clearly a dummy: There are no bayonet tabs, or electrical contacts. Yet if it keeps that shallow register distance and wide throat (seemingly about 42 mm in their mockup) it will be much friendlier to lens adapters than the Samsung NX mount. Leica lenses on an affordable APS-C sensor, anyone?

Of course Sony has a history of imposing proprietary standards on customers (think Memory Stick or MiniDisc’s ATRAC). We shouldn’t assume the camera will even turn on, if it can’t find a properly-coded Sony lens on the front.

And Sony’s concept has no control dials visible at all. Maybe it would be a touchscreen-driven interface. Meh.

There was one bright note of hope for me in this PMA however. And that’s a bit of a convergence in comments from several different photo executives.

A Samsung VP expressed surprise how many NX10 buyers were opting for the 30mm pancake, rather than the kit zoom.

Actually this doesn’t surprise me at all: In any indoor lighting, the f/2 lens is vastly preferable to the zoom (which is 2 stops slower at 30mm).

And the pancake ridiculously small. Plus, the little guy tests pretty well too.

Meanwhile, Sigma’s chief has started seeing that in Asian markets, even non-techie consumers are buying fast primes. They want that glamorous, shallow depth of field look—even for family snaps, or blogging what they cooked last night.

And finally, Ned Bunnell (president of Pentax’s US division, and also a blogger) was quoted as saying,

“I don’t have to be paid to say this, I really enjoy our small compact cameras and I actually adore our Limited [prime] lenses. I’m not a zoom type of photographer, and so I love our 31mm, I love all of our compact lenses, because it suits the way I was trained as photographer”

and:

“[W]e are finding a lot of people who maybe are more serious photographers who have bought the K-x, and now on the forums are asking about our Limited lenses.”

Well all right then! Three different executives suddenly think prime lenses are good. (Photographers do seem to have limped along with them OK, during those first 85 years of film cameras.)

So maybe we have a groundswell on our hands: Say goodbye to chubby, dim zooms; and hello to small, perky, and bright primes!

But… er, Ned? The FA 31mm is an oversized holdout from the film era; it costs almost $1000.

I can’t find a price quoted yet for Samsung’s pancake. But the µ4/3 pancakes are $280 (the f/2.8 Olympus) and $400 (the f/1.7 Panasonic).

The Sigma 30mm f/1.4 (newly-beloved of Asian moms) is $440.

So, why can’t Pentax build a small, fast “normal” for the APS-C format?

Better have a pancake and think it over.

Dear Panasonic,

February 17, 2010

I’m sorry I called you a crackhead, really.

It was just a little joke. Can we still be friends?

Recently, we all learned that your Lumix GH1 has the best sensor of any Micro Four Thirds camera. That’s great!

And I think the native multi-aspect-ratio feature is awesome too. (You do that nicely on several cameras, like the LX3.)

But the only way you’re letting us purchase the GH1 is in a kit with a hulking, slow superzoom. That lens sold on its own costs $850, so I’m sure this really drives up the price of the combo.

The GH1 has great HD video capabilities, and I understand that the zoom is optimized for this purpose (with quieter motors, etc.)

But but for stills photography, the GH1 also has class-leading high ISO performance. Available-light shooters would surely appreciate a smaller body that can still deliver the goods at ISO 800.

I’m one of them.

So as an alternative, why not also bundle the GH1 with your excellent 20mm f/1.7 pancake?

Shaky Photoshopping of GH1 and Pancake

The 20mm is over two and a half stops faster! And presumably, you could offer a GH1 kit for a lot less money then. Like $400 less.

It would also make the combo dramatically smaller and less obtrusive. And the pancake’s “wide-normal” 40e focal length is actually one I find exceptionally handy.

You might sell a few extra GH1’s that way.

sincerely,

—petavoxel