“Full Frame” Unfulfilled

August 10, 2010

If you put any faith in DxO Mark scores (and I do understand their limitations), today’s best $500 DSLRs make better images than all of the sub-$4000 cameras sold until 2008. Largely that’s thanks to some good recent APS-C sensors from Sony.

So I’m not sympathetic towards certain Pentax users, who bleat that they can’t make adequate photographs—not until the company delivers a DSLR with a 24×36 mm sensor. (With pre-Photokina Pentax rumors swirling, the issue is once again a hot topic for discussion.)

Full-Frame Pentax?

Yes, many long-time Pentaxians do have investments in full-frame “FA” lenses, ones that could cover the format.

But keep in mind, over the history of photography there have many camera mounts which died out entirely—obsoleting numerous fine lenses. How about Contax/Yashica mount? Minolta MD, or Canon FD? (Or even earlier systems, such as Exakta or the superb Zeiss Contarex?)

By contrast, any Pentax lens made since 1983 can at least be used on a modern DSLR—metering automatically, and with the benefit of built-in shake reduction. So the handwringing that some great lenses have been “orphaned” by Pentax can get a bit exaggerated.

Some point out hopefully that not long ago, Pentax introduced new telephoto lenses bearing the FA designation. Ergo, full-frame is coming!

But truthfully, no decent lens design even breaks a sweat in covering an image circle much smaller than its focal length. With a telephoto, full-frame coverage is basically “free”—so why not go ahead and use the FA labeling? It allowed Pentax to finesse the format question for a while longer; and maybe even sold a couple of extra lenses to Pentax film-body users.

I do agree with the complaint that the viewfinders of most consumer DSLRs are puny and unsatisfying. The view through the eyepiece of a full-frame body is noticeably more generous.

However, the electronic viewfinder of an Olympus E-P2 neatly solves this problem too—at a price savings of about $1400 over today’s cheapest full-frame DSLR. And the EVIL wave is only gathering momentum.

The perpetual cry from full-frame enthusiasts is that Moore’s Law will eventually slash 24x36mm sensor pricing. To me, this seems like a wishful misunderstanding of the facts.

The shrinking of circuit sizes which permits faster processors and denser memory chips is irrelevant to sensor design—the overall chip dimensions are fixed, and the circuitry features are already as small as they need to be.

Also, figuring the costs of CMOS chip production is not entirely straightforward. It costs money to research and develop significant new improvements over prior sensor generations; it’s expensive to create the photolithography masks for all the circuit layers. Then, remember that all these overhead costs must be recouped over only two, perhaps three years of sales. After that, your sensor will be eclipsed by later and even whizzier designs.

Thus, there is more to a sensor price than just the production-line cost; it also depends on the chip quantities sold. And full-frame DSLRs have never been huge sellers.

If APS-C sensors prove entirely satisfactory for 95% of typical photographs (counting both enthusiasts and professionals), a vicious circle results. With no mass-market camera using a full-frame sensor, volumes stay low, prices high. But with sensor prices high, it’s hard to create an appealing camera at a mass-market price point.

Furthermore, let’s consider the few users who would actually benefit from greater sensor area.

For the few who find 12 megapixels inadequate, nudging the number up to 24 Mp is not the dramatic difference you might imagine. To double your linear resolution, you must quadruple the number of pixels. Resolution-hounds would do better to look to medium format cameras, with sensors 40 Mp and up—which conveniently, seem to be dropping towards the $10,000 mark with the release of Pentax’s 645D.

The last full-frame holdouts are those who need extreme high-ISO potential. There’s no doubt that the 12Mp full-frame Nikon D3s makes an astounding showing here, with high-ISO performance that’s a solid 2 f/stops better than any APS-C camera. This is a legitimate advantage of class-leading 24×36 mm sensors.

Yet aside from bragging rights, we have to ask how many great photographs truly require ISO 6,400 and above. ISO 1600 already lets us shoot f/1.7 at 1/30th of a second under some pretty gloomy lighting—like the illumination a computer screen casts in a darkened room.

A day may come when sensor technology has fully matured, and every possible sensitivity tweak has been found. At that point, a particular sensor generation might hang around for a decade or more. So might those long production runs permit much lower unit costs for a full-frame sensor? There will still be a full-frame surcharge simply from the greater surface area and lower chip yields.

But who knows, perhaps it’s possible? By then we may have 40 Mp, 24×36 mm chips that are our new new “medium format.”

Pentax: Sensors or Lenses?

May 30, 2010

On Pentaxian discussion boards, one dispute that absolutely refuses to die is whether Pentax will (or should) introduce a “full frame,” 24x36mm sensor DSLR.

The pleading for 24×36 often comes from those who might have already invested heavily in earlier FA lenses—meaning, ones originally designed to cover the old 135 film format.

I understand the emotion here—it’s quite true that an APS-C sensor wastes some of the capabilities of those lenses. And let’s take it as given that Pentax’s engineers would be fully capable of producing an excellent 24×36 camera.

But does Pentax “owe” its existing customers such a model?

Whither Pentax?

May 7, 2010

I guess this was the week for Pentax’s European executives to go rogue.

Hiroshi Onoda made some comments to the Spanish Pentaxeros website, hinting at future “more professional” DSLRs (google translation). Then, Stephen Sanderson told the UK’s Amateur Photographer that Pentax “hadn’t ruled out” a mirrorless, EVIL model.

Both statements were vague and ambiguous enough to set off a storm of speculation on Pentaxian discussion boards. Many hearts fluttered, imagining Pentax might introduce a DSLR based on a 24 x 36mm “full frame” sensor; others wondered whether they might join Olympus and Panasonic in the Micro Four Thirds camp.

Pentax Surprises Ahead?

But there’s two key facts that must always be remembered about Pentax:

- They do not make their own sensor chips

- Last year, the company almost went under

At PMA 2010, Pentax USA president Ned Bunnell gave an interview with Imaging Resource. He said plainly that Hoya, Pentax’s new corporate owners, were demanding more focus on the bottom line, and a clearer marketing strategy.

So, Pentax simply cannot build every camera its fanbase thinks might be cool.

Making Peace With APS-C

March 19, 2010

It’s shocking to realize it was only six years ago when the first digital SLRs costing under $1000 arrived.

The original Canon Digital Rebel (300D) and Nikon D70 were the first to smash that psychologically-important price barrier. These 6-megapixel pioneers effectively launched the amateur DSLR market we know today.

But one argument that raged at the time—and which has never completely gone away—was about the “crop format” APS-C sensor size. (The name derives from a doomed film system; but now just means a sensor of about 23 x 15 mm.)

Was APS-C just a temporary, transitional phase? Would DSLRs eventually “grow up,” and return to the 24 x 36 mm dimensions of 135 format?

This was a significant question, at a time when virtually all available lenses were holdovers from manufacturers’ 35mm film-camera systems.

The smaller APS-C sensor meant that every lens got a (frequently-unwanted) increase in its effective focal length. Furthermore, an APS-C sensor only uses about 65% of the film-lens image circle. Why pay extra for larger, heavier, costlier—and possibly dimmer—lenses than you need?

Also, after switching lens focal lengths to get an equivalent angle of view, the APS-C camera will give deeper depth of field at a given distance and aperture. (The difference is a bit over one f/stop’s worth.)

But a more basic question was simply: Do APS-C sensors compromise image quality?

Well, sensor technology (and camera design) have gone through a few generations since 2004.

Microlenses and “fill factors” improved, so that even higher-pixel-count sensors improved sensitivity. (For one illustration, notice how Kodak practically doubled the quantum efficiency of their medium-format sensors between a 2007 sensor and the current one selected for the Pentax 645D.)

Today’s class-leading APS-C models can shoot with decent quality even at ISO 1600. And the typical APS-C 12 megapixel resolution is quite sufficient for any reasonable print size; exceeding what most 35mm film shooters ever achieved.

So it’s clear that APS-C has indeed reached the point of sufficiency for a the great majority of amateur photographers.

Still, Canon and Nikon did eventually introduce DLSRs with “full frame” 24 x 36 mm sensors. They were followed by Sony, then Leica. In part, this reflects the needs of professional shooters, whose investments in full-frame lenses can be enormous.

And for a few rare users, files of over 20 megapixels are sometimes needed. In those cases, a full-frame sensor maintains the large pixel size essential for good performance in noise and dynamic range.

But these are not inexpensive cameras.

So the question has never completely gone away: Is APS-C “the answer” for consumer DSLRs? Or will full-frame sensors eventually trickle down to the affordable end of the market?

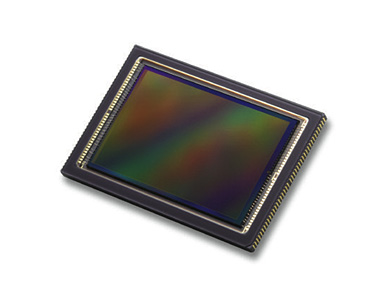

Canon Full-Frame Sensor

I have mentioned before an interesting Canon PDF Whitepaper which discusses the economics of manufacturing full-frame sensors (start reading at pg. 11).

It’s not simply the 2.5x larger area of the sensor to consider; it’s that unavoidable chip flaws drastically reduce yields as areas get larger. Canon’s discussion concludes,

[…] a full-frame sensor costs not three or four times, but ten, twenty or more times as much as an APS-C sensor.

However, since that 2006 document was written, I have been curious whether the situation has changed.

More recently I found a blog post from 2008 which sheds more light on the subject. (Chipworks is an interesting company, whose business is tearing down and minutely analyzing semiconductor products.)

Note that one cost challenge for full-frame sensors is the rarity of chip fabs who can produce masks of the needed size in one piece. “Stitching” together smaller masks adds to the complexity and cost of producing full-frame sensors—Chipworks was doubtful that the yield of usable full-frame parts was even 50%.

Thus, Chipwork’s best estimate was that a single full-frame sensor costs a camera manufacturer $300 to $400! (This compares to $70-80 for an APS-C sensor.)

And that’s the wholesale cost. What full-frame adds to the price the consumer pays must be higher still.

Thus, it seems unlikely the price of a full-frame DSLR will ever drop under $1000 (that magic number again)—at least, not anytime soon.

And actually, APS-C pretty darned decent.

So let’s embrace APS-C. That means it’s time to reject overweight, overpriced lenses that were designed for the older, larger format. We need to demand sensible, native lens options.

It would have been nice if APS-C had somehow acquired a snappier, less geeky name—maybe that’s still possible?

But it seems time to declare: It’s the standard.